"The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes."

At the Vatican Museums last summer, I witnessed something both miraculous and terrifying: a room full of tourists experiencing the Sistine Chapel without actually being in the Sistine Chapel. They sat in ergonomic chairs, wearing sleek headsets, their heads tilted back in the same angle of wonder as their counterparts in the real chapel a few buildings away. The virtual tourists paid €20 for their experience. The physical tourists paid €150 and waited three hours in line. Both groups claimed to have "seen" the Sistine Chapel. Both groups were wrong.

But the real story wasn't in either room. It was in the gift shop between them, where a young woman who had just finished her virtual tour argued with her friend about whether they needed to see "the real thing" at all. "I've already seen every detail," she insisted, waving her hand dismissively at the signs pointing toward the actual chapel. "The resolution in VR is actually better than human vision." Her friend, unconvinced, walked alone to join the physical queue. In that casual dismissal of reality in favor of its digital double, I glimpsed our cultural future, and it was terrifying.

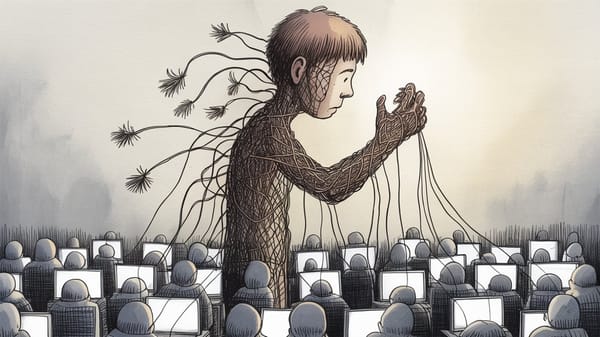

This is not another Luddite screed against technology, nor a romantic plea for the "authentic" travel experiences of yesteryear. This is a warning about something far more insidious: the quiet death of experiential consciousness and the rise of what I call "digital cultural colonialism." We're not just changing how we see the world; we're fundamentally altering what it means to experience it at all.

The virtual tourism industry, worth $24 billion and growing, sells itself as the great democratizer of travel. Anyone, anywhere, can now "visit" the world's wonders. A teenager in rural Kansas can "walk" through the Louvre. A retiree in Bangkok can "explore" Machu Picchu. A teacher in Lagos can take their class on a "tour" of the British Museum. The quotation marks in the previous sentences aren't just literary flourish – they're warnings. Each set of quotation marks represents a boundary between experience and simulation that the industry is determined to erase.

When Mark Zuckerberg recently proclaimed that virtual tourism would "break down the barriers between cultures," he wasn't wrong – he was terrifyingly right. Like a cultural neutron bomb, virtual tourism doesn't destroy the physical structures of the world's heritage sites; it simply eliminates the actual human experience within them. The buildings remain; the consciousness dissolves.

Consider what happens in your brain during actual travel. Neuroscientists have identified unique neural patterns that emerge from the friction of real cultural encounter – the mild anxiety of not speaking the language, the spatial disorientation of unfamiliar architecture, the sensory overload of new smells and sounds. These patterns, these moments of productive discomfort, quite literally reshape our neural pathways. Virtual tourism, in its quest for frictionless experience, eliminates precisely these transformative elements.

The industry's response to such criticism is revealing in its blindness. "But the technology is getting better!" the Silicon Valley prophets proclaim. "Soon we'll be able to simulate everything – temperature, smell, texture, even the feeling of getting lost!" This is rather like saying that if we make a mirror perfect enough, we can step through it. The problem isn't the quality of the simulation; it's the fundamental nature of consciousness itself.

Last month, I visited a leading VR research laboratory where engineers were perfecting what they called "complete sensory tourism." The system included temperature control, directional audio, haptic feedback, and even carefully calibrated scent dispersal. It was impressive technology. It was also, in its attempt to perfectly replicate reality, missing the entire point of travel. The researchers were so focused on simulating the feeling of ocean spray on your face at the Cliffs of Moher that they forgot to ask what it means to actually stand at the edge of a continent, feeling your own mortality in the wind.

Here's where it gets darker. As virtual tourism becomes more sophisticated and physical travel becomes more expensive, we're creating a new kind of experiential apartheid. The wealthy will continue to have transformative encounters with real places and cultures, building the kind of emotional and cultural intelligence that comes only from genuine cultural friction. Everyone else will get an algorithmic approximation of experience, a digital ghost of reality.

This division is already more pronounced than most realize. While basic virtual tourism experiences become increasingly accessible – a decent VR headset now costs less than a budget airline ticket to Europe – the cost of actual international travel has risen by 40% in the past five years. More significantly, the time required for physical travel has become its own kind of luxury. The ability to spend two weeks exploring Rome's back alleys or wandering Kyoto's temple gardens is increasingly reserved for those with both financial and temporal wealth.

UNESCO, in its well-meaning embrace of virtual preservation, has become an unwitting accomplice in this cultural flattening. When they celebrated the complete digital mapping of Palmyra after its destruction by ISIS, they called it a "victory for cultural preservation." But what exactly are we preserving? The form without the context? The image without the sacred? The sight without the site?

The technical achievement is impressive, but the philosophical implications are chilling. We're creating a world where the physical experience of culture becomes a luxury good, while the rest of humanity gets a Netflix-style catalog of places to "visit" – complete with personalized recommendations and a "skip intro" button for the boring historical parts.

This isn't just cultural elitism disguised as technological progress; it's a fundamental shift in human consciousness. Virtual tourism platforms don't just mediate our experience of places; they mediate our understanding of what it means to experience anything at all. When everything is accessible, nothing is encountered. When every place is instantly reachable, no place is actually arrived at.

I recently spoke with Dr. Maria Hernandez, a cognitive anthropologist studying the impact of virtual tourism on cultural understanding. Her research reveals something troubling: virtual tourists often develop what she calls "simulation confidence" – a false sense of cultural competence based entirely on digital experiences. "They know every street in Marrakech's medina from virtual tours," she explained, "but they've never experienced the cultural negotiation of buying a carpet, the sensory overwhelm of the spice markets, or the disorientation of truly foreign experience."

This simulation confidence has real-world implications. Corporate executives who've done virtual site visits make decisions about remote locations they've never physically visited. Architecture students design buildings for climates they've never actually felt. Cultural preservation boards make decisions about sites they've only experienced through headsets. Each instance represents a kind of cultural malpractice, a substitution of data for experience.

The environmental argument for virtual tourism is seductive in its apparent rationality. Why burn jet fuel to visit the Great Barrier Reef when you can see it in perfect detail from your living room? Why contribute to the overcrowding of Venice when you can explore its canals in virtual solitude? This logic ignores a crucial truth: the purpose of travel isn't just to see things, but to be changed by them.

The industry's response to such criticism is to point to the accessibility benefits of virtual tourism, the preservation of fragile sites, the opportunities for those who could never afford to travel. These are valid points, but they ignore a crucial question: What if the ability to truly encounter different cultures, to experience the transformative friction of real travel, becomes yet another luxury reserved for the elite?

The solution isn't to abandon virtual tourism but to radically rethink it. Instead of creating digital mirrors of physical places, we should be developing entirely new categories of human experience. Imagine virtual spaces that don't pretend to replace physical travel but instead prepare us for it, enhance our understanding of it, or offer entirely different modes of cultural encounter.

Some innovative projects are pointing the way. The "Temporal Tourism" initiative in Kyoto allows virtual visitors to experience not just places but time periods, following the lives of historical figures across centuries. The "Cultural Consciousness Project" in Berlin creates virtual experiences that intentionally heighten rather than eliminate the friction of cultural encounter. These approaches suggest a different future for virtual tourism – not as a replacement for physical travel but as a new category of human experience entirely.

The technology itself isn't neutral. Each virtual tourism platform makes countless decisions about what to show and what to hide, what to simulate and what to simplify. When a VR experience of Jerusalem's Old City lets users "skip" through crowded markets or "mute" the call to prayer, it's making editorial decisions about what constitutes the essential experience of place. These aren't just technical choices; they're acts of cultural curation that shape how millions of people understand and relate to other cultures.

Consider the implications of this curation at scale. When a major virtual tourism platform decides to "clean up" the streets of Calcutta or "enhance" the colors of a Caribbean sunset, they're not just adjusting pixels – they're reshaping global perceptions of place and culture. The danger isn't that these virtual experiences are fake; it's that they're becoming more influential than reality in shaping how we understand the world.

This digital sanitization of experience has political implications too. Virtual tourism platforms, mostly developed by Western tech companies, inevitably embed Western perspectives and preferences in their simulations. The way they frame monuments, choose historical narratives, or prioritize certain aspects of culture over others represents a new form of cultural colonialism – one that operates not through physical occupation but through the control of virtual experience.

The stakes are enormous. In a world increasingly divided by cultural misunderstanding, the ability to truly encounter and comprehend different cultures cannot become a luxury good. If we allow virtual tourism to replace rather than supplement real cultural encounter, we risk creating a world where authentic experience becomes the ultimate mark of privilege – a world where some people experience reality while others merely consume its digital reflection.

We're already seeing the emergence of what I call "experience markets" – where authentic cultural encounters are packaged and priced like luxury goods.

Want to learn traditional pasta-making from an Italian nonna? That's $500. Prefer to watch a 4K VR recording of the same experience? That's $15.99. The pricing isn't just about access; it's about the commodification of authenticity itself.

The college student in the Vatican Museums' virtual Sistine Chapel may have seen every detail of Michelangelo's frescoes in perfect resolution. But she missed something essential – the very thing that makes travel transformative. As we rush to digitize every corner of human experience, we must ask ourselves: Are we democratizing access to the world's wonders, or are we commodifying consciousness itself?

The answer may determine not just the future of tourism, but the future of human experience itself. The real threat isn't that virtual tourism will replace physical travel; it's that we'll forget the difference between seeing and experiencing, between accessing and understanding, between consuming culture and encountering it.

In the end, the virtual tourist sees everything but experiences nothing. And in a world where experience itself becomes a luxury good, we all become poorer, even as our digital libraries of places to "visit" grow ever larger. The tragedy isn't that we're creating simulations of the world's wonders; it's that we're creating a generation that might prefer them.

Courtesy of your friendly neighborhood,

🌶️ Khayyam

Knowware — The Third Pillar of Innovation

Systems of Intelligence for the 21st Centurty

Member discussion