According to Aldous Huxley,

"Experience is not what happens to you; it's what you do with what happens to you."

What haunts me is watching our tech industry chase perfect simulations while reality fades to background. At a VR conference last month, brilliant minds obsessed over rendering digital raindrops while actual rain fell unnoticed outside. Back home, they would call this 'mistaking the menu for the meal.'

From Richard Sutton's insights on reinforcement learning to Pine and Gilmore's experience economy, evidence suggests that authentic engagement resists being reduced to data points. This essay explores why different cultural approaches to embodied learning might offer wisdom our digital abstractions miss.

Ultimately, breaking free from our digital flatland—embracing the full dimensionality of reality rather than perfecting its simulation—may be our most crucial challenge as we enter what could truly become the Age of Experience.

Beyond the Digital Flatland

Saskatchewan: where the sky teaches what algorithms can't.

I grew up in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan—the land of the living skies also known as The Flatlands. So it comes as no surprise from pure immersion what a digital flatland looks like.

Edwin Abbott's 1884 tale "Flatland" has always resonated with me, maybe because I spent my childhood staring across those endless Saskatchewan prairies. Abbott's two-dimensional inhabitants couldn't grasp the concept of three-dimensional space—much like how we seem trapped in our own digital flatland today. We're trying to squeeze intelligence and meaning into flattened representations, while real understanding might require something closer to those vast, complex skies I grew up under.

This limitation of our digital world becomes clearer when we look at two fields that might seem unrelated at first glance. Back in 1998, B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore noticed something interesting: modern economies were increasingly valuing staged experiences over traditional goods and services. Around the same time, in the AI world, Richard Sutton's research suggested something similarly profound – systems that learn through direct experience tend to outperform those built on pre-programmed human knowledge. While these insights come from different worlds, they might be telling us something important: there's something about authentic engagement that resists being reduced to simple data points.

Think about how a squirrel learns to navigate tree branches. It doesn't study physics equations or watch YouTube tutorials—it just jumps, falls, scrambles, and tries again. Sutton would argue this messy, direct engagement with the world contains something essential that our most sophisticated AI systems are missing. As he puts it, "If we understood a squirrel, we'd be almost all the way there" to understanding human intelligence. "The language part is just a small veneer on the surface." Pine and Gilmore discovered something parallel in business: the experiences we remember most vividly aren't the ones that simulate reality perfectly, but the ones that engage us across multiple dimensions—sight, sound, touch, emotion, surprise.

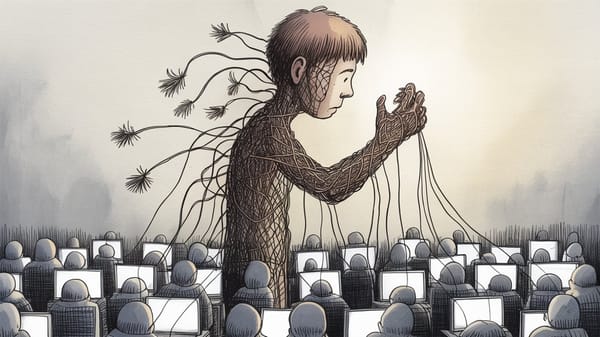

But here's where we keep falling into the same trap Abbott described. We flatten everything. Large language models treat human conversation like sequences of tokens—imagine trying to understand a prairie storm by reading weather data instead of feeling the wind change direction. Sutton frames this limitation clearly: "Just to mimic what people say is not really to build a model of the world at all. You're mimicking things that have a model of the world, the people. But I would question the idea that they have a world model... They have the ability to predict what a person would say. They don't have the ability to predict what will happen." Virtual experiences might look real, but they miss those subtle dimensions you can't digitize: the weight of air in a room, the way silence feels different in different spaces.

What's interesting is how different cultures seem to grasp this instinctively. East Asian economies have long emphasized collective experience and learning through practice rather than theory. Take Japan's concept of "ba"—these shared physical spaces where knowledge gets created through actual interaction, not virtual meetings. It suggests that maybe some wisdom about authentic experience got lost in our rush toward digital everything.

Here's the paradox that keeps me up at night: the more technologically capable we become, the further we seem to retreat into our digital flatland. It's like we're getting better and better at building more sophisticated prisons. As Sutton observes, "Large language models learn from something else. They learn from 'here's a situation and here's what a person did.' And implicitly, the suggestion is you should do what the person did." This creates a fundamental limitation - there's "no goal... no ground truth" in this approach. Without a goal, "there's no right thing to say." Maybe the solution isn't more realistic simulations—maybe it's stepping back toward direct experience, both for AI and for ourselves.

I'm starting to think the future won't belong to whoever builds the most convincing simulations. It'll belong to those who can create genuine opportunities for direct engagement—with all the messiness and unpredictability that entails. This Age of Experience isn't just a technological shift. It's philosophical, maybe even spiritual. We need to remember what those Saskatchewan skies taught me: sometimes the most important dimensions are the ones you can't measure.

The Limits of Abstraction

Here's what bothers me about our current AI breakthroughs. Yes, GPT-4 can solve calculus problems that would stump most college students. Google's PaLM can reason through complex scenarios with impressive sophistication. But strip away the impressive outputs and you're left with statistical pattern matching across flattened text—like trying to understand Michelangelo's David by staring at a photograph.

Sutton calls this "The Bitter Lesson," and the bitterness comes from a hard truth: there may be no shortcuts to genuine understanding. As he puts it, "What we want is a machine that can learn from experience. Where experience is the things that actually happen in your life. You do things, you see what happens. And that's what you learn from."

It's the same problem Pine and Gilmore spotted in business decades ago. Selling coffee beans is one thing—creating that "third place" feeling at Starbucks is something entirely different. One's about commodity exchange, the other's about crafting an experience that touches multiple senses and emotions simultaneously. Processing text tokens might get you impressive chatbots, but understanding the world? In Sutton's view, that requires "learning from experience. You try things, you see what works. No one has to tell you." Most crucially, it requires "a goal. So without a goal, there's no sense of right or wrong or better or worse." That seems to require something more like sitting in that coffee shop, feeling the warmth of the cup, hearing conversations blend into ambient noise.

Global Perspectives on Embodied Learning

This tension between abstraction and experience isn't just theoretical—it's playing out differently across global AI research communities. Chinese AI researchers, drawing on traditional concepts of practical wisdom (实践智慧), are increasingly betting on embodied learning. Places like the Beijing Institute of Technology are building robots that learn manufacturing skills the old-fashioned way—through practice, failure, and gradual improvement. It's apprenticeship for machines, which sounds almost poetic when you think about it.

Meanwhile, Europe's taking a more cautious approach that I find intriguing. Their AI Act actually requires real-world testing facilities for high-risk systems—basically admitting that you can't predict how AI will behave just by running simulations. It's regulatory humility, which is rare and refreshing.

The Japanese approach might be my favorite, though. They're applying concepts like "ba" and "kata" to machine learning—principles that guide martial arts training where knowledge emerges through physical practice. This aligns perfectly with Sutton's observation that "the basic animal learning process is for prediction and for trial and error control." In this view, "supervised learning is not something that happens in nature," and our most advanced AI systems still lack this fundamental capability that "all mammals have." Companies like Preferred Networks are teaching robots complex tasks through repetitive physical practice, the way a karate student might perfect a kata through thousands of repetitions. There's something beautiful about machines learning through what amounts to meditation in motion.

Beyond Simulation: The Return to Reality

Breaking free from the digital flatland requires a fundamental reimagining of how we approach both AI development and human experience design. This transformation demands more than just technological innovation – it requires a philosophical shift in how we understand learning and engagement.

Companies like Boston Dynamics achieve breakthrough results by prioritizing real-world interaction over simulation. Their robots learn through physical engagement with their environment, much like the squirrel Sutton describes—not through studying physics equations, but through direct interaction: jumping, falling, scrambling, and trying again. As Sutton emphasizes, "Intelligence is about understanding your world... reinforcement learning is about understanding your world. Whereas large language models are about mimicking people, doing what people say you should do. They're not about figuring out what to do." The success of their Atlas robot, which can perform parkour and complex acrobatic maneuvers, demonstrates the power of learning through direct physical interaction.

Similarly, the most successful experience businesses create value not through virtual simulations but through carefully crafted real-world engagements. Disney's theme parks succeed not because they perfectly simulate fantasy worlds, but because they create authentic emotional experiences in physical space. This principle extends beyond entertainment venues to emerging fields like experiential retail, immersive education, and therapeutic environments. It reflects what Pine and Gilmore recognized decades ago about the distinction between commodity exchange and crafting experiences that engage multiple senses and emotions simultaneously. Companies like Meow Wolf and TeamLab are pioneering new forms of physical-digital hybrid experiences that engage all senses while maintaining authentic human connection.

Implications for the Future

This convergence of insights from experience design and AI research points to a fundamental shift in how we should approach both fields:

- Learning Environments: Future AI development will require sophisticated physical spaces for learning through direct experience, environments where systems can develop what Sutton calls "a model of the physical world" by predicting "what will happen" rather than merely "what a person would say."

- Value Creation: Businesses must move beyond digital simulation to create authentic, multidimensional experiences that engage all senses and capabilities.

- Global Competition: Nations and companies that best facilitate real-world learning and authentic experience will lead the next wave of innovation.

- Technological Evolution: Hardware development may shift focus from processing power to sensory richness and physical interaction capabilities.

Embracing Full-Dimensional Reality

Growing up under Saskatchewan's infinite sky taught me something Abbott's Flatlanders never learned: sometimes you have to lift your eyes from the flatland to see what's really possible. As we stand at what Sutton describes as "a major stage in the universe, a major transition" from replication to design, we face a profound philosophical choice. Sutton frames this transition as potentially "the transition from the world in which most of the interesting things are replicated" to a world where "everything will be done by design and construction rather than by replication." As we enter this new Age of Experience, success won't come from building better simulations—it'll come from remembering that reality has dimensions our digital flatland can't capture. The future belongs to those brave enough to step off the prairie of pixels and into the full dimensionality of the real world.

Whether we're developing artificial intelligence or designing human experiences, the lesson is the same: there are no shortcuts through the Digital Flatland. As Sutton reminds us, in a truly intelligent system, "the content of the knowledge is statements about the stream" of experience—predictions about what will happen when actions are taken. "Because it's a statement about the stream, you can test it by comparing it to the stream and you can learn it continually." This fundamental connection to reality is what our digital abstractions often miss. True intelligence, like true value, emerges only through direct engagement with the rich, messy, multidimensional reality of the physical world.

The challenge ahead isn't just technological – it's philosophical and practical. We must decide, as Sutton puts it, whether to view emerging intelligence as "our offspring" that we "should be proud of" and "celebrate their achievements," or as something alien that should provoke horror. This perspective is "a choice" with profound implications. As we pursue this "major stage in the universe," we should perhaps embrace Sutton's view that "we should be proud that we are giving rise to this great transition in the universe." We must move beyond our fascination with digital abstraction to embrace the full complexity of real-world experience. In doing so, we might not just create better AI or better businesses; we might finally begin to understand intelligence itself.

References and Citations

Foundational Theory

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). "Welcome to the Experience Economy." Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97-105.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). "The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage." Harvard Business School Press.

- Sutton, R. S. (2019). "The Bitter Lesson." Incompleteideas.net, March 13, 2019.

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). "Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction." MIT Press, 2nd Edition.

Embodied Cognition and Learning

- Clark, A. (2015). "Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind." Oxford University Press.

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (2016). "The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience." MIT Press, Revised Edition.

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). "The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception." Houghton Mifflin.

Cultural Perspectives

- Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). "The Concept of 'Ba': Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation." California Management Review, 40(3), 40-54.

- Nisbett, R. E. (2004). "The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently... and Why." Free Press.

AI and Technology

- Brooks, R. A. (1991). "Intelligence Without Representation." Artificial Intelligence, 47(1-3), 139-159.

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2017). "Building Machines That Learn and Think Like People." Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, e253.

Dimensional Theory and Experience

- Abbott, E. A. (1884). "Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions." Seeley & Co.

- Norman, D. A. (2013). "The Design of Everyday Things." Basic Books, Revised Edition.

Recent Research and Applications

- Battaglia, P. W., et al. (2018). "Relational Inductive Biases, Deep Learning, and Graph Networks." arXiv:1806.01261.

- Ha, D., & Schmidhuber, J. (2018). "World Models." arXiv:1803.10122.

Industry Evidence

- Boston Dynamics. (2021). "Learning Through Physical Interaction." Technical White Paper Series.

- Disney Imagineering. (2019). "The Architecture of Staged Experiences." Corporate Research Publication.

Policy and Regulation

- European Commission. (2021). "Artificial Intelligence Act." COM/2021/206 final.

- Ministry of Science and Technology of China. (2021). "Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan."

Don't miss the weekly roundup of articles and videos from the week in the form of these Pearls of Wisdom. Click to listen in and learn about tomorrow, today.

Sign up now to read the post and get access to the full library of posts for subscribers only.

Khayyam Wakil grew up in Saskatchewan, where the endless prairie skies shaped his perspective on dimensions beyond the digital flatland. His research explores the intersection of experiential learning and artificial intelligence, with a focus on how direct engagement creates understanding that simulations cannot replicate. His work draws from both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions while examining how different cultures approach the relationship between experience and knowledge. When not contemplating, he can be found playing chess in Union Square, engaging in the kind of direct, unpredictable interactions that, as Richard Sutton might note, algorithms still struggle to understand.

Member discussion