"Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas."

— John Locke, who would have been deeply disturbed to discover that neurons apparently come with their own rough drafts already sketched in invisible ink.

The Challenge to Our Assumptions

The pre-configured mind…

Why Brain Organoids Are Dismantling Our Understanding of Intelligence

When neurons in a laboratory dish begin firing in patterns that look suspiciously like they're processing sensory information—despite never having experienced sight, sound, or touch—well, it's the kind of finding that makes you pause mid-coffee and wonder if we've been thinking about intelligence all wrong.

A recent study in Nature Neuroscience from UC Santa Cruz reveals findings that should probably make both neuroscientists and AI researchers a bit uncomfortable: Brain organoids, grown from stem cells with no sensory input whatsoever, spontaneously develop electrical firing patterns nearly identical to those found in sensory processing regions of mature brains. These aren't random sparks—they're organized, temporally structured sequences that seem to be rehearsing for a world they've never encountered. Which, frankly, is a little unsettling.

Now, I might be overstating the implications here, but I think most of the scientific community is missing something pretty significant.

The False Choice We've Been Forced to Make

For decades, the nature versus nurture debate has trapped us in a binary prison. You know the drill: either our minds start as blank slates that experience writes on, or they're essentially pre-programmed by our genes. This new research doesn't really settle that old argument—it might actually blow it up entirely by pointing toward a third possibility we've somehow overlooked.

The brain doesn't start as a blank slate OR a finished blueprint. Maybe it starts as something more like a pre-configured template—sort of waiting to be filled in through experience.

Here's what gets me about this. These organoid neurons are firing in patterns that look like they're processing visual information, but there's no visual system. They're generating temporal sequences that resemble auditory processing, but there's no sound. It's almost like the architecture isn't learning to process information so much as it's getting ready to process specific types of information—before that information even shows up.

Which is, you have to admit, pretty different from both traditional learning and genetic determinism.

Why This Should Reshape AI Development

Most of machine learning operates on a pretty straightforward assumption: show an algorithm enough data, and intelligence will emerge. Feed a neural network enough examples, and it'll figure out patterns and build some kind of internal model of the world.

But what if that's backwards?

What if biological intelligence doesn't actually build models from scratch? What if it's more like filling in pre-existing templates through experience? The difference isn't just semantic—it's computational. And it might explain why human babies can learn so much more efficiently than our best AI systems.

Take object permanence—that basic understanding that things don't just vanish when you can't see them anymore. Most babies get this by around 8 months, and they certainly haven't seen millions of examples. Meanwhile, our AI systems struggle with this concept even after training on vast image datasets. Maybe that's because they're trying to learn it from scratch.

But what if human brains don't learn object permanence? What if neural circuits come pre-wired to expect that objects persist, and experience just calibrates those built-in expectations?

The organoid study seems to suggest something along these lines: maybe our brains come pre-loaded with architectural constraints that make some kinds of learning almost effortless and others nearly impossible. We might not be general learning machines at all—more like specialized pattern matchers with pretty specific templates.

The Biological Architecture of Intelligence

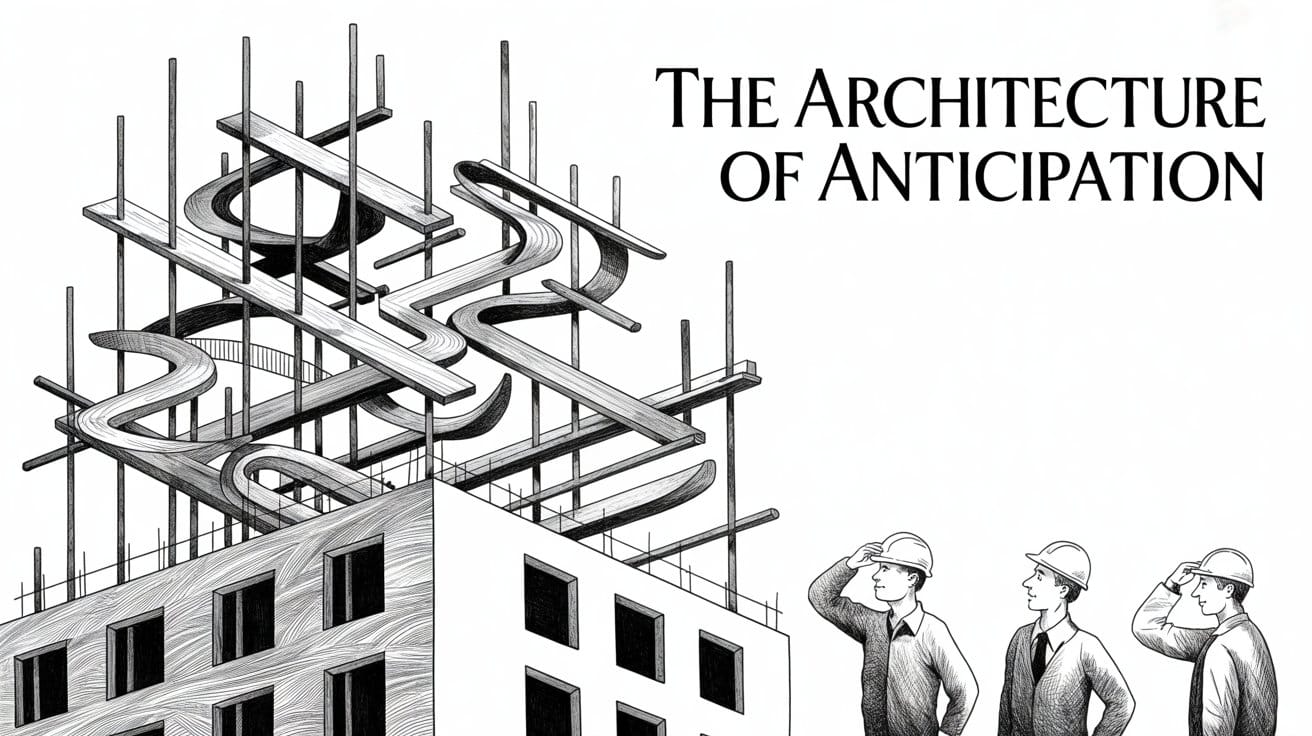

The Three Layers Nobody's Discussing

What the organoid findings seem to reveal is a three-layer structure that goes beyond the old nature-versus-nurture split:

Layer 1: Substrate Architecture - The physical wiring constraints determined by genetic expression during development. Call it the hardware, if you want.

Layer 2: Dynamic Templates - The spontaneous firing patterns that emerge from local neuron interactions, creating temporal and spatial structures before any sensory input. Think of it as firmware, maybe.

Layer 3: Information Scaffolding - The proto-semantic structures that these patterns encode, creating meaning-shaped holes that experience will fill. It's like a file system sitting there waiting for data to arrive.

Most current AI architectures handle Layer 1 pretty well—we're good at designing network structures. Sometimes we even touch Layer 3 through pre-training on massive datasets. But Layer 2? That spontaneous emergence of functional templates from local interactions? We're barely touching that.

And maybe that's why our AI systems need so much data and break so easily. They're missing the middle layer that seems to make biological learning actually work.

What Evolution Actually Optimized For

Here's what I think we've been getting wrong: evolution probably didn't optimize for general learning ability. It optimized for learning efficiency by basically pre-wiring neural circuits with specific expectations about how the world works.

When you think about it, this makes complete sense evolutionarily. A baby antelope that needs millions of examples to figure out that lions are dangerous doesn't pass on its genes. Natural selection would have favored organisms whose brains already expected predators, food sources, social hierarchies—and could fine-tune those expectations quickly with just a bit of experience.

I mean, we've sort of known this in theory. But watching it happen in organoids—seeing neurons that have never processed anything spontaneously organize into patterns that look ready to handle specific types of information—it hits differently. It makes it real.

So maybe the brain isn't this general-purpose learning machine that evolution gave really good algorithms. Maybe it's more like a collection of specialized templates that evolution pre-configured, and learning mostly just calibrates and refines those templates for wherever you happen to find yourself.

The Self-Assembly Problem

Right now, a lot of AI researchers are really excited about model-based reinforcement learning—basically the idea that smart agents should build internal models of their environment and use those models to plan ahead. It's elegant, it works pretty well, but the organoid study suggests we might be approaching this backwards.

The traditional approach assumes agents experience the world, build internal models from those experiences, simulate possible futures, and pick actions based on those simulations.

But if neurons are already firing in patterns that look like world models before they've experienced anything, then maybe biological model-based learning isn't about building models from scratch—it's about filling in templates that are already there.

The computational difference here is huge. Building from scratch? You need tons of data, long training times, and the whole thing is fragile—it forgets things, breaks when conditions change.

Filling in a pre-configured template? You need way less calibration data, things specialize quickly, the core structure stays robust, and it generalizes naturally within whatever domain the template was designed for.

Maybe that's why babies learn so efficiently. They're not trying to solve the whole model-building problem from scratch—they're solving a much simpler template-filling puzzle.

Why Model-Based Reinforcement Learning Needs Rethinking

Right now, a lot of AI researchers are really excited about model-based reinforcement learning—basically the idea that smart agents should build internal models of their environment and use those models to plan ahead. It's elegant, it works pretty well, but the organoid study suggests we might be approaching this backwards.

The traditional approach assumes agents experience the world, build internal models from those experiences, simulate possible futures, and pick actions based on those simulations.

But if neurons are already firing in patterns that look like world models before they've experienced anything, then maybe biological model-based learning isn't about building models from scratch—it's about filling in templates that are already there.

The computational difference here is huge. Building from scratch? You need tons of data, long training times, and the whole thing is fragile—it forgets things, breaks when conditions change.

Filling in a pre-configured template? You need way less calibration data, things specialize quickly, the core structure stays robust, and it generalizes naturally within whatever domain the template was designed for.

Maybe that's why babies learn so efficiently. They're not trying to solve the whole model-building problem from scratch—they're solving a much simpler template-filling puzzle.

The Broader Implications

What This Means for Consciousness

Okay, let's talk about the elephant in the room. If our thoughts are largely pre-configured—if the neural patterns that make up our inner lives are somehow rehearsed before we're even born—what does that mean for consciousness? For free will? For the whole experience of being, well, us?

These organoid neurons are firing in organized patterns that seem to encode information, but they're obviously not conscious. I mean, they can't be—we're talking about a few millimeters of tissue in a petri dish. But those same patterns, if you scaled them up and embedded them in a body with sensory systems and the ability to act in the world, might be the neural basis of conscious experience.

Maybe consciousness isn't really about the patterns themselves—it's about those patterns being instantiated in a system that can actually interact with the world. Empty templates sitting in a dish aren't conscious, but filled templates, integrated into a body and environment? That might be a different story.

This has some pretty significant implications for AI consciousness. Maybe no matter how sophisticated our neural networks become, they won't achieve genuine consciousness if they're missing these pre-configured templates that biological systems apparently start with. We might be able to build systems that look intelligent without ever creating systems that actually experience their own intelligence.

Or—and this possibility keeps me up at night—maybe consciousness requires a specific developmental path that you can't just skip. It might not be about ending up with the right architecture, but about going through the right sequence of changes to get there.

The Uncomfortable Clinical Implications

Tal Sharf, who led this study, thinks this could change how we approach neurodevelopmental disorders. If the earliest neural firing patterns are already setting the stage for later brain function, then genetic or environmental disruptions might leave traces much earlier than we've realized.

But let's be honest about what this might mean: if neural templates are largely pre-configured, then a lot of what we think of as cognition, personality, maybe even mental health, could be substantially locked in before birth. How much therapy, education, and environmental changes can actually reshape these templates becomes a real question—with potentially uncomfortable answers.

We'd like to believe that with the right interventions, anyone can develop any skill, overcome any limitation, achieve any goal. The pre-configured brain suggests this might be wishful thinking. Some patterns could be so deeply wired that changing them is almost impossible. Others might be malleable, but only during very specific developmental windows.

This doesn't mean we should give up on intervention—it means we might need to be much more precise about when and how we try to help. But it also means accepting that some limitations might be built into the architecture itself, not just the result of bad experiences.

Future Forward Perspectives

What We Need to Build Instead

If this research is pointing us in the right direction—and the evidence is getting pretty compelling—then maybe we need to seriously rethink how we're approaching artificial intelligence.

Stop fighting architectural priors. The machine learning community often treats built-in biases as problems to solve. But biological intelligence suggests we've got this backwards: the right architectural biases might be exactly what makes efficient learning possible. Maybe we should be embracing strong priors instead of trying to eliminate them.

Study self-assembly mechanisms. Instead of hand-designing every aspect of our architectures, we probably need to understand the local interaction rules that somehow lead to functional global organization. This is a completely different research program from what most of deep learning is doing right now.

Accept developmental trajectories. Some aspects of intelligence might need to develop through specific stages, not just train until convergence. The order and timing of how circuits form could be just as important as what they end up looking like.

Recognize template domains. Human intelligence probably isn't truly general—it's more like a collection of specialized templates for different domains. Maybe we should stop chasing monolithic general intelligence and start building systems with domain-specific templates that can be filled in efficiently.

Take embodiment seriously. The organoids generate patterns that look sensory, but they're not actually processing real sensations. Genuine intelligence might need that feedback loop between prediction and reality that you only get through actual embodiment.

The Question We Can't Avoid

The organoid study forces a question I'm not sure we're ready for: what if everything we think we know about learning, intelligence, and how minds develop is basically backwards?

What if intelligence isn't mostly about learning algorithms, but about templates that are already there? What if the real challenge isn't building good world models, but efficiently filling in the right templates? What if consciousness needs developmental paths we don't know how to create?

These aren't just philosophical questions anymore. They're empirical questions that organoid research is actually starting to answer. And the answers aren't what any of us expected.

Those neurons in petri dishes are firing in patterns that look suspiciously like thinking—before any experience that could possibly have shaped thought. They're not blank slates. They're not pre-programmed machines either. They're something else entirely, something we don't really have good frameworks for understanding yet.

Until we figure out what that something else is, we might be building our AI systems on completely wrong assumptions.

The pre-configured mind isn't just an interesting neuroscience finding—it's throwing down a gauntlet to everything we think we know about intelligence. The question is whether we're actually ready to pick up that gauntlet.

Don't miss the weekly roundup of articles and videos from the week in the form of these Pearls of Wisdom. Click to listen in and learn about tomorrow, today.

Sign up now to read the post and get access to the full library of posts for subscribers only.

About the Author

Khayyam Wakil is an inventor and systems architect who grew up in Saskatchewan. He designs infrastructure, systems of intelligence, maps failure modes, and builds things that don't break under pressure. His recent breakthrough in reinforcement learning—emerged from patterns he first recognized simulating the operations of a grocery store, watching too much. television, and the slow torture of growing up in Saskatchewan.

Khayyam has spent two decades in tech, building platforms that scale, optimizing processes that seemed unoptimizable, and solving coordination problems that seemed unsolvable. His work on true model-based reinforcement learning demonstrates how biological principles can transform artificial intelligence. Khayyam understands how systems work, how they fail, and what happens when the feedback loops run faster than the humans inside them can adapt.

He writes about the intersection of technology and society, usually from the skeptical perspective of someone who's seen how quickly efficiency gains can become human losses. This essay represents 20.56% AI assistance and 79.44% human insight—a ratio he's tracking because it matters, and because he suspects it won't stay that way for long.

For speaking engagements or media inquiries: sendtoknowware@protonmail.com

Subscribe to "Token Wisdom" for weekly deep dives and round-ups into the future of intelligence, both artificial and natural: https://tokenwisdom.ghost.io

#AI #artificialIntelligence #neuroscience #brain #organoids #ethics #innovation #reinforcementlearning #futureofwork #research #responsibleAI #consciousness #longread | 🧮⚡ | #tokenwisdom #thelessyouknow 🌈✨

Member discussion